Affiliate Disclosure: VPNexp.com is reader-supported. We may earn a commission if you purchase a VPN through links on our site. This does not affect our rankings or recommendations.

Deep Dive by Country (2026 Updates)

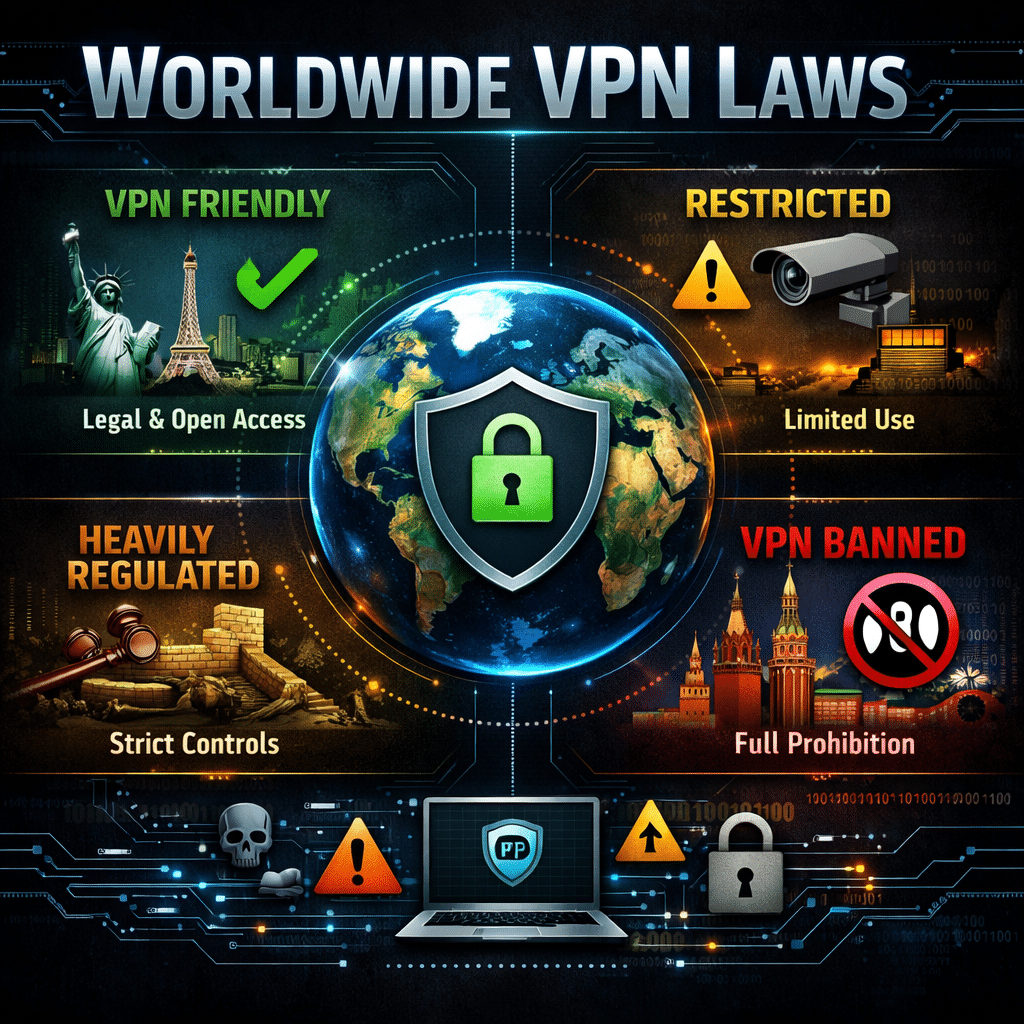

Where are VPNs legal — and where can using one put you at risk? The answer depends heavily on where you live, how your country regulates telecom traffic, and whether privacy tools are treated as normal consumer software or services that require state oversight. This 2026 guide walks through how VPN laws, data-retention rules, and online privacy frameworks differ around the world, so you understand what’s allowed, what’s restricted, and what to consider before you connect.

This guide draws on independent research, reputable legal commentary, digital-rights reporting, and technology-policy analysis — along with long-term user-reported experiences across different regions. It is a practical overview, not legal advice, and policies may change, especially in states with evolving information-control frameworks.

Table of Contents

- Why VPN Laws Matter in 2026

- How “Legal vs Restricted” Really Works

- VPN Laws & Online Privacy Rules by Country / Region

- Comparison Tables: Regions at a Glance

- Real-World Considerations When Using a VPN Abroad

- Pricing, Subscriptions & Real-World Value

- How We Researched This Guide

- FAQ & Decision Guidance

Why VPN Laws Matter in 2026

VPNs have gone from niche security tools to mainstream utilities. Remote work, public Wi-Fi, fragmented streaming catalogs, and constant data collection mean more people lean on VPNs for privacy and safer connections. In many countries, they’re as uncontroversial as password managers. In others, they sit at the intersection of national security, information control, and telecom regulation — which is where things get complicated.

From a user’s perspective, the stakes are simple: you want to know whether installing and using a VPN is allowed, whether encrypted traffic attracts the wrong kind of attention, and whether your provider is subject to aggressive logging or disclosure rules. Laws rarely mention specific brand names or apps, so people are left reading between the lines of cybercrime statutes, data-retention mandates, and platform-control regulations.

In 2026, the gap between “legal in theory” and “safe in practice” is wider in some regions than others. A VPN may be technically permitted but heavily monitored; in other countries, it may be unregulated but frequently blocked on campus, in offices, or by streaming platforms. Understanding the broad pattern in your country — and in the places you travel — helps you use VPNs realistically rather than magically.

How “Legal,” “Restricted,” and “Heavily Controlled” Should Be Understood

When people ask “Are VPNs legal?” they’re usually blending three different questions into one:

- Is VPN software itself legal to download and use? (Installation and basic use.)

- Are specific uses illegal even with a VPN? (Fraud, hacking, harassment, piracy, bypassing state blocks, etc.)

- Do authorities restrict who can provide VPN services? (Licensing, approved providers, mandatory logging.)

In most countries, VPNs themselves are legal tools. What matters is what you do with them. Crimes remain crimes, whether or not there’s an encrypted tunnel between you and the website you’re using. However, a handful of governments regulate VPN providers directly through licensing, data-retention mandates, or requirements to block certain websites. In those places, unapproved VPNs may be blocked or discouraged, and users sometimes report that enforcement is unpredictable.

For this guide, we use three plain-language labels in each country section:

- Legal – VPNs are broadly legal to use; misuse of any tool can still be prosecuted.

- Legal with restrictions / conditions – VPNs are legal, but providers or usage may be affected by data-retention, licensing, or platform rules.

- Heavily restricted / controlled – Consumers are expected to use only approved or licensed services; unapproved VPNs may be blocked, discouraged, or risky.

These labels summarize common interpretations from legal commentary and digital-rights reporting; the fine print is always more complex, but they give you a practical starting point.

VPN Laws & Online Privacy Rules by Country / Region

Below you’ll find a high-level breakdown for 20+ major internet-using countries and regions. The focus is on consumer VPN use, not on niche enterprise scenarios. Enforcement can be uneven, and new rules can appear quickly, so treat this as a snapshot rather than a permanent verdict.

United States

Status: Legal

VPNs are widely used in the U.S. for remote work, corporate security, privacy, research, and travel. There is no law that generally bans VPNs. Instead, the legal environment revolves around how data is handled (for example, by ISPs and tech platforms) and how law enforcement can access records with proper legal process. Policy debates continue around surveillance powers and telecom metadata, but they don’t typically target ordinary VPN users.

In practice, most Americans can sign up for and use mainstream VPN services without interference. Some workplaces, schools, and streaming platforms block or throttle VPN traffic, but that’s a network or contract issue, not a criminal one. Illegal activity — such as fraud, harassment, or hacking — remains illegal regardless of encryption.

Canada

Status: Legal

Canada’s approach is broadly similar to the U.S., with VPNs widely used by individuals, businesses, universities, and government agencies themselves. Federal and provincial privacy laws, plus telecom and cybercrime rules, shape how data is processed and when it can be disclosed. Independent legal commentary generally describes Canada as permissive towards VPNs, while still enforcing laws against misuse.

Most users report straightforward access to consumer VPNs. Restrictions are more likely to appear at the network level: for example, workplace policies that block unfamiliar VPN endpoints or require company-managed clients instead of personal services.

European Union (General Overview)

Status: Legal

Across the EU, VPNs are legal and widely adopted, both by consumers and by organizations that need secure remote access. The region’s privacy backbone is GDPR, which sets strict rules on personal data handling and encourages data minimization and purpose limitation — values that align naturally with privacy-oriented VPN services.

Where things get nuanced is data-retention and surveillance. Some member states have pushed for broad metadata retention at the ISP level, while courts have repeatedly narrowed what’s permissible. The result is a patchwork where VPNs are legal everywhere, but the overall privacy posture (and expectations around data retention) can vary country by country.

United Kingdom

Status: Legal

The UK allows VPN use and sees extensive adoption across business and consumer segments. At the same time, investigatory-powers laws give authorities avenues to request information in defined circumstances. That doesn’t make VPNs illegal; it simply means that, as in many countries, providers can be required to cooperate with lawful investigations.

For everyday users, the experience is straightforward: VPNs are available, app stores list major providers, and there is no general prohibition on using them. The key is to treat a VPN as a privacy tool, not as a guarantee of absolute secrecy or an invitation to ignore other laws.

Germany

Status: Legal

Germany is often seen as one of Europe’s more privacy-conscious jurisdictions. VPNs are legal and commonly used, and German courts have been central in limiting overly broad data-retention mandates. That doesn’t mean there is no surveillance, but it does mean that laws are frequently tested for proportionality and fundamental-rights compatibility.

From a user standpoint, consumer VPNs are easy to access and operate normally. Illegal behavior, especially around cybercrime or extremist content, remains subject to enforcement, but simply encrypting your traffic is not in itself suspect.

France

Status: Legal

France allows VPN use, and you’ll find plenty of French-language marketing from major providers. However, the country also maintains strong national-security and counter-terrorism frameworks, including surveillance powers that can be used under defined conditions. These powers target serious threats rather than consumer privacy tools in general.

For most residents and travelers, using a VPN in France looks like using one anywhere in Western Europe: it’s a standard option for securing connections at cafés, hotels, universities, and co-working spaces.

Netherlands

Status: Legal

The Netherlands has long been home to data centers and infrastructure providers, and VPNs are fully legal. Dutch courts and regulators have played a role in EU-level conversations about data retention and law-enforcement access. The general trend is that broad, indiscriminate retention mandates face legal challenges, while targeted investigations remain possible.

Everyday VPN use — for privacy, P2P traffic, or bypassing local network shaping — is common and widely accepted, with enforcement focused on specific unlawful conduct, not on encryption as such.

Spain

Status: Legal

Spain follows the wider EU pattern: VPNs are legal, data protection is governed by GDPR and local implementation, and telecom providers have obligations around security and lawful access. Spanish users can choose from international services and local brands, and VPN advertising is common.

As elsewhere, what matters most is how you use the tool. Using a VPN to secure coffee-shop Wi-Fi or shield browsing data from your ISP is a mainstream use case. Using any tool to facilitate fraud or harassment remains illegal.

Italy

Status: Legal

Italy permits VPN use, and Italian-language VPN guides are easy to find. As with other EU countries, you’ll see a mix of GDPR-based privacy protections, telecom rules, and cybercrime laws. Independent analysis typically characterizes Italy as a standard EU jurisdiction in which VPNs are part of normal digital life.

Streaming platforms, employers, and universities may still limit VPN traffic based on their own policies, but at the legal level, everyday VPN use is not prohibited.

India

Status: Legal with regulatory conditions

India does not ban VPNs, and they are widely used by individuals and businesses. However, policy shifts in recent years have introduced notable friction. Certain regulations requested VPN providers to log specific user data and retain it for defined periods. Some global VPN services responded by removing Indian-based servers or adjusting their operations to avoid keeping logs domestically.

For users, the experience often involves connecting to virtual locations that are “India-optimized” but physically hosted elsewhere. This allows providers to avoid local logging expectations while still offering access to India-related content. The environment is best described as legal but policy-sensitive, and India remains a closely watched jurisdiction for digital-rights advocates.

China

Status: Heavily restricted / controlled

China operates one of the most sophisticated internet-control frameworks in the world. Only government-approved or licensed VPN services are allowed to operate, typically for business-grade connectivity. Many unapproved consumer VPNs are blocked, and traffic that attempts to bypass centralized filtering may be throttled or disrupted.

Travelers and residents report that access to foreign VPN services can fluctuate. In some cases, tools work intermittently; in others, they fail outright. The broad takeaway from digital-rights reporting is clear: China is one of the strictest environments for VPN use, and users should be cautious about assumptions around anonymity or impunity.

Quick reminder: In heavily controlled environments like China, a VPN should never be treated as a shield against local law. Even if a foreign service connects, you may still be subject to platform blocks, monitoring, or penalties — and rules can change quickly.

Japan

Status: Legal

Japan allows VPN use and has a strong culture of corporate and academic remote access, where VPNs are routine. Privacy rules and telecom regulations exist, but they don’t target VPNs as a technology. Consumers use VPNs for streaming, gaming, and privacy on public networks, and app stores host major providers without issue.

As in many advanced economies, enforcement focuses on clear cybercrime or abuse, not on whether someone has encrypted their Netflix session at a hotel.

South Korea

Status: Legal

South Korea is a highly connected country where VPNs are legal and commonly used. Regulatory attention tends to focus on online content, gaming rules, and cybercrime rather than on VPNs themselves. Users frequently use VPNs to access foreign content libraries, protect traffic on public Wi-Fi, or maintain access to services while abroad.

Network-level policies in workplaces and schools may restrict VPN use, but there is no general ban on the technology.

Singapore

Status: Legal with close regulatory monitoring

Singapore permits VPNs and has a large base of corporate and consumer users, but it also maintains robust cybercrime, media, and national-security laws. Content and speech regulations can be stricter than in some Western jurisdictions, and there is a strong emphasis on order and compliance.

In practice, residents routinely use VPNs for security and access to global services. However, observers generally recommend that users treat Singapore as a jurisdiction where online conduct — with or without a VPN — is more closely regulated than in some other countries.

Indonesia

Status: Legal with content controls

VPNs are not broadly banned in Indonesia, and many people use them to access social networks, news sites, and streaming platforms. However, the government has rules allowing it to request blocks on certain services or content, and platforms sometimes must comply with local takedown and licensing requirements.

Digital-rights groups describe Indonesia as a mixed environment: VPN tools themselves are widely used, but content control and platform regulation can affect what you can access, regardless of encryption.

Vietnam

Status: Legal in practice, with tight content regulation

Vietnam does not have a clear, general ban on VPNs, and users report that many services work. However, the country enforces strict rules on online speech, data localization, and platform cooperation, particularly around political content and national security. Social media companies and other platforms are expected to comply with local requests and regulations.

Using a VPN for privacy or streaming is widespread; using any tool to organize activities that violate local speech or security laws carries risk. That distinction is especially important for journalists, activists, and politically active users.

Australia

Status: Legal

Australia permits VPN use and has a mature market of providers and customers. The country does have data-retention rules for telecom providers and legislation allowing certain forms of law-enforcement access, which have been debated by privacy advocates. But none of that makes VPNs themselves off-limits.

Australians frequently use VPNs to access overseas streaming libraries, secure travel Wi-Fi, and mitigate ISP-level tracking. Streaming platforms may still restrict content by region, but that’s handled through platform policies rather than criminal law.

New Zealand

Status: Legal

New Zealand’s environment is broadly similar to Australia’s: VPNs are legal, used by consumers and businesses, and treated as normal security and privacy tools. The country has its own privacy and telecom rules, but there is no general prohibition on encryption-based services.

For travelers, New Zealand is typically classified as a very VPN-friendly destination: connections to major providers are stable, app-store access is normal, and enforcement focuses on genuinely harmful conduct rather than on VPN usage.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

Status: Legal for permitted uses, with strict misuse penalties

In the UAE, VPNs themselves are not banned. Businesses and individuals often use them for legitimate purposes like securing company systems or accessing international services. However, laws make it an offense to use “fraudulent computer network protocols” to commit or conceal crimes, and the penalties can be serious.

Digital-rights organizations and legal commentators often summarize the UAE position as: using a VPN for lawful purposes is allowed; using it to commit or hide illegal acts can aggravate the offense. Users should be particularly cautious about misrepresenting their location in ways that affect regulated services or violate local law.

Saudi Arabia

Status: Legal in practice, with strong content and platform controls

Saudi Arabia does not explicitly ban VPNs, and users report that many services function. However, the country enforces extensive content restrictions and closely regulates speech, media, and online platforms. Authorities can block websites and services and pursue enforcement against content deemed illegal.

Using a VPN to secure traffic on hotel Wi-Fi or access bank accounts is common. Using any tool to distribute prohibited content or organize illegal activity is risky, and VPNs do not change that calculus.

Turkey

Status: Restricted, with periodic blocks

Turkey has a history of selectively blocking social media platforms and messaging apps during periods of political tension or security incidents. VPNs themselves are not universally banned, but authorities have at times moved to restrict or block specific providers that help users bypass access limits.

User reports suggest a mixed environment: some VPN services work consistently; others experience disruptions. Legal analysis often recommends that users treat Turkey as a jurisdiction where access conditions can change quickly, especially around politically sensitive events.

Brazil

Status: Legal

Brazil combines a large online population with active debates about platform responsibility, content moderation, and data protection. VPNs are legal and widely used for streaming, gaming, and privacy. Brazil’s general data protection law (LGPD) governs how organizations handle personal data, with obligations similar in spirit to GDPR.

VPN use is not inherently controversial; enforcement typically targets harmful conduct or non-compliance by platforms, not encryption tools by themselves.

Mexico

Status: Legal

Mexico allows VPN use, and adoption has been growing among both consumers and businesses. Legal frameworks address data protection, cybercrime, and telecom regulation, but there is no broad ban on VPN technology. As in many countries, the main risks relate to how a VPN is used, and whether that use overlaps with illegal activities.

For travelers, Mexico is generally seen as a VPN-friendly destination, especially for securing connections in hotels and cafés and accessing accounts from abroad.

Argentina

Status: Legal

Argentina offers legal VPN use, with a data-protection regime and telecom regulations that mirror patterns seen in many other Latin American countries. VPNs are used for privacy, streaming, and remote work. There is no general ban on encryption, and app stores list major VPN providers as usual.

Enforcement again focuses on harmful activities rather than on the presence of a VPN app on a device.

Nigeria

Status: Legal in practice, with episodic platform tensions

Nigeria has a large and growing online population. VPNs are legal and widely used, especially among younger, urban users. There have been high-profile disputes between authorities and social media platforms in recent years, during which VPN adoption spiked as people sought to maintain access.

While there is no consistent ban on VPNs, digital-rights groups note that the broader environment can be unpredictable, and users should pay attention to local developments that affect platforms or speech.

South Africa

Status: Legal

South Africa allows VPN use and has a developed legal framework for privacy, data protection, and telecom regulation. VPNs are common among businesses, journalists, and privacy-conscious consumers. App stores list popular VPN services, and there is no general ban or licensing regime for consumer tools.

Travelers typically report trouble-free VPN usage for banking, streaming, and work connections, with the usual caveats around local network quality and platform policies.

Comparison Tables: Regions at a Glance

The tables below simplify a lot of nuance, but they offer a useful snapshot. The first focuses on regional status; the second groups specific countries into permissive, conditional, and restrictive categories so you can see patterns quickly.

| Region | Status Summary | Typical User Experience |

|---|---|---|

| North America | Legal | Broad consumer access; occasional workplace or streaming blocks |

| EU / EEA | Legal | Strong data-protection rules; VPNs are mainstream tools |

| UK | Legal | Legal VPN use; investigatory powers govern targeted access |

| Asia-Pacific | Mixed | From very permissive (Japan, Australia) to heavily controlled (China) |

| Middle East | Mixed | VPNs often legal; misuse and speech laws can carry high penalties |

| Latin America | Mostly legal | VPNs widely used; attention focused on platform conduct |

| Africa | Mostly legal | Growing VPN adoption; platform disputes in some states |

| Country / Region | Category | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| US, Canada, EU states, UK, Australia, New Zealand | Permissive | VPNs are standard privacy tools; crimes remain illegal regardless of VPN use |

| India, Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Nigeria | Conditional | VPNs generally legal, but platform rules, speech laws, or data mandates matter |

| China, Russia (increasingly), selected other tightly controlled states | Restrictive | Approved or licensed VPNs only; unapproved tools may be blocked or risky |

Real-World Considerations When Using a VPN Abroad

Legal status is only part of the story. How using a VPN actually feels in day-to-day life depends just as much on network controls, platform policies, and enforcement culture. You could be in a legally permissive jurisdiction where your workplace VPN is still blocked, or in a more restrictive jurisdiction where the law is strict on paper but enforcement focuses on specific shock events.

- Corporate and campus networks can block VPN tunnels to enforce security or compliance policies. That doesn’t make VPNs illegal — it just means you’re on someone else’s network with their rules.

- Streaming platforms may clamp down on region-hopping regardless of local law. If a service detects a VPN, it may refuse playback or limit content even where VPNs are fully legal.

- Hotels, airports, and cafés sometimes throttle or interfere with VPN traffic, intentionally or due to misconfigured firewalls. User reports often note that switching protocols or ports can help.

- Heavily controlled states may shift from tolerating certain tools to blocking them with little notice, especially around elections, protests, or sensitive anniversaries.

Across all these contexts, a VPN should be seen as a privacy and security enhancer, not as a free pass. It can reduce the exposure of your traffic to opportunistic snooping and ISP-level logging, but it doesn’t make you invisible or exempt from local law.

Pricing, Subscriptions & Real-World Value

Most leading VPNs follow a familiar subscription model: pay monthly at a relatively high rate, or commit to a one- or two-year plan to bring the average monthly cost down. Industry comparisons suggest that “value” is less about shaving off the last dollar and more about long-term trust: does the provider explain what it logs, where it’s based, and how it handles legal requests?

Some quick rules of thumb:

- Look beyond price. A very cheap VPN with vague policies may be worse than no VPN at all.

- Check device limits. If you have a family or many devices, simultaneous-connection caps matter.

- Consider your travel pattern. If you spend a lot of time in restrictive regions, protocol agility and obfuscation features can be more important than a few megabits of extra speed.

- Plan for the long term. Multi-year plans only make sense if you’re comfortable with the provider’s track record and business model.

Refund windows, upgrade options, and add-ons like dedicated IPs or password managers vary widely. Many users start with a shorter plan, test performance along their usual routes, then commit to a longer subscription once they know what to expect.

How We Researched This Guide

Instead of relying on a single jurisdiction or one person’s travel anecdotes, this guide draws on a mix of sources: legal commentary, digital-rights reporting, telecom and technology-policy analysis, and user-reported patterns shared over time. Laws and enforcement cultures are complex, so the emphasis here is on clear, conservative summaries rather than edge-case loopholes.

We did not run formal legal reviews in every country — that would be a different kind of project entirely — and nothing here should be treated as individualized advice. The goal is to help you frame the right questions: “Is VPN use broadly accepted here?”, “Does this country license providers?”, “Are there known platform blocks?”, and “How careful should I be about assuming a VPN makes me invisible?”

FAQ & Decision Guidance

Is using a VPN illegal anywhere?

In most of the world, VPNs are legal. A smaller group of countries either license providers tightly (for example, allowing only government-approved services) or periodically block unapproved tools. Even in permissive regions, using a VPN to carry out clearly illegal activity doesn’t change the underlying legality of the act itself.

Can authorities tell that I’m using a VPN?

Often, yes. Even without seeing the contents of your traffic, network operators can usually recognize that you’re sending encrypted data to a known VPN endpoint. That doesn’t automatically create legal risk in most countries, but in tightly controlled environments, visible VPN traffic can draw more scrutiny than ordinary connections.

Should I avoid installing a VPN before traveling to restrictive countries?

Many travelers prefer to set up tools before they arrive, since app stores or websites may be limited on local networks. At the same time, in heavily controlled states, it’s wise to keep a low profile, avoid discussing circumvention tools publicly, and stay within local law and local expectations.

Does a VPN make me anonymous?

No. A good VPN can hide your traffic from your ISP, reduce location-based tracking, and make it harder for casual observers to profile you — but it doesn’t remove browser fingerprints, account-level identifiers, payment trails, or the possibility of legal requests to the provider. Think in terms of reducing data exposure, not achieving perfect anonymity.

What’s the safest way to use a VPN in countries with gray or shifting rules?

Stick to clearly lawful activities, avoid drawing attention to circumvention, keep your software updated, and be prepared for sudden service disruptions. If you rely on specific apps or platforms, have backups (offline maps, downloaded content, alternative communication channels) so a VPN outage doesn’t become a crisis.

Bottom-line decision guidance: in most countries, choosing a reputable VPN is a sensible part of a broader security and privacy toolkit. In restrictive environments, the stakes are higher, and a VPN should be used with caution and awareness of local law — not as a magic cloak that overrides it.